Environmentalism - What Counts, and Who’s Counting?

One of the ironies of environmentalism is the lack of human diversity in a discipline utterly devoted to protecting and preserving diversity. While opening doors to invite diversity in is critical, opening our minds to what environmentalism is, and how people actively engage in it is equally important. The American myth that “black people don’t do outdoors,” has deep and complex origins. It is not a simple landscape, and we ignore that landscape at our peril. As America becomes less white, environmental leadership and participation needs to reflect that. Otherwise, who will steward the land? People of color routinely engage in conservation and provide extraordinary environmental leadership in every corner of the globe. It is the mainstream recognition and valuation of it that falls short. These four stories are a tiny piece of a global narrative aching to be told.

Carolyn Finney is the author of Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors. As a cultural geographer and professor, Finney explores how issues of difference impact participation in decision-making processes designed to address environmental issues. Her work seeks to develop greater cultural competency within environmental organizations and institutions.

Last month, Finney took a bold stand for environmentalism when she and 8 others resigned in protest from the U.S. National Parks Service Advisory Board. One year earlier, the NPS, EPA and other federal agencies were issued a climate change gag-order as goals of extracting and exploiting natural resources replaced goals of preserving public lands. As of January 2018, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke had yet to take a meeting with the NPS advisory board. Finney refused to participate in her own marginalization.

“I resigned this week because I cannot be overlooked, and I will not be silenced through inattention. I must continue to honor the ideals of commitment, service, and responsibility that I first learned from my father and continue to see expressed in those with whom I’ve been privileged to work on the National Parks Advisory Board and in the National Park Service.”

Why doesn't every American know this?

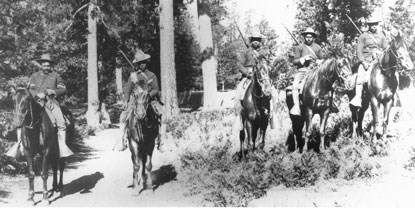

Few Americans know that nearly 500 African American soldiers literally helped build, manage, and maintain the U.S. National Park System in its infancy. Sequoia National Park had little access for the general public until the segregated regiments of “Buffalo Soldiers” hand-built the roads into Giant Forest that are still used today. They also constructed the first trail to the top of Mt. Whitney (the tallest peak in the contiguous U.S.). Under the leadership of Colonel Charles Young, the first African American National Park Superintendent, those men patrolled Kings Canyon, Sequoia and Yosemite in the summer on horseback. Yellowstone and Glacier National parks were also under their watch. Park Ranger Sheldon Johnson is their biggest champion and he keeps their story alive through tireless research and multi-faceted presentations. When Johnson first stumbled upon an 1899 park photo of 5 of the original troops, he told the Associated Press that the discovery was like “stumbling into your own family while traveling in a foreign country.”

Despite this legacy, Finney’s father, a Korean War veteran, was turned away and told "We don't hire negroes," when he tried to apply for a job as a park ranger upon returning to civilian life. He subsequently took a job as caretaker on 12 acres of land that he went on to steward for 50 years. In a 2014 interview with Francie Latour, Finney called her parents “the first conservationists I ever knew.” And yet, in a 2006 letter announcing that the land on that estate was now preserved in perpetuity via a conservation easement, there was no mention of her parents’ decades-long stewardship.

“They were thanking the new owner for his conservation-mindedness,” Finney said. “In reading it, I couldn’t help thinking, where was the thanks to my parents, who cared for that land for 50 years? That got me thinking about all the people in our history whose stories are unsung or invisible. We don’t hear about them because nobody calls that conservation. They don’t fit into the way we talk about environmentalism in the mainstream.”

Changing the narrative IS environmentalism.

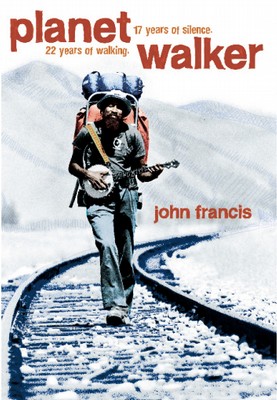

In 1971, John Francis, witnessed an 800,000-gallon oil spill in the San Francisco Bay when two Standard Oil tankers collided. First, he helped clean it up. Then, he gave up motorized transportation and began walking as a simple act of protest. Twenty-two years later, he was still walking. Seventeen of those years were in silence. His simple act of protest evolved into an experiment of a new way of interacting with the world … by listening. As he walked across the USA in silence, he stopped in Montana to earn a Master’s degree in Environmental Studies and in Wisconsin to earn a PhD in Land Resources. He continued to walk on and sail through the Caribbean and South America in silence.

The cover of John Francis's book

The cover of John Francis's book

When the Exxon Valdez spilled 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound, Alaska, Francis broke his silence to serve as project manager for the US Coast Guard staff writing the regulations for the Oil Pollution Act of 1990.

Studying the environment through academics, while experiencing it deeply through walking and silence, transformed his vision of what “the environment” is. In a 2011 interview with Daniel Fromson of The Atlantic, Francis said he believes the thing that has the biggest impact on how people think about sustainability is how we think about each other.

“The environment is therefore also about human rights, civil rights, gender equality, economic, and education equity. It is about all the ways we relate to one another because how we relate to each other manifests itself in the physical environment around us.”

The physical manifestations of changed relationships

Powerhouse change-maker Majora Carter gets it. She stewards the land by stewarding its people. The South Bronx native views urban renewal through an environmental lens as she draws a direct connection between ecological, economic, and social degradation.

Her determination to "Green the ghetto!” helped create Hunts Point Riverside Park, the first open-waterfront park the South Bronx in 60 years. She parlayed that initial win into securing $1.25 million in federal funds for a greenway along the South Bronx waterfront.

Measuring success by standards that redefine who pays and who benefits, Carter’s economic consulting and planning firm aims for what she calls a “triple bottom line” where returns are shared equally between the developer, government, and the community. This model rewards stakeholders, not just shareholders. Cleaner air, access to healthy food, climate readiness, green jobs, economic development, appropriate transportation, and a better quality of life are just some of the consequences of the eco-friendly sustainable development envisioned by Carter. Those standards aren’t the norm, but they are taking root.

As the demographics of America change, so must its ideas and institutions. Cultivating diversity within those institutions is essential to maintaining healthy ecosystems and thriving communities.

ecological restoration, community action